The dark side of the Guggenheim Museum in Abu Dhabi

Andrew Ross: “There’s always a whiff of corruption when so much public funding is allocated to a private beneficiary”

Text: David Henderson eta Txema García

Photos: Andrew Ross

A social activist and professor of Social and Cultural Analysis at New York University, Andrew Ross was a co-founder of the Gulf Labor Coalition, which for five years pressured Western cultural brands — including the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation — both in the United Arab Emirates (Abu Dhabi) and in Helsinki to ensure the protection of workers subjected to inhumane labor conditions. Originally from Scotland and a supporter of its independence, he explains how these major brands operate in their new forms of cultural and economic colonization, often in cooperation with local governments. A word of warning now that this Foundation has set its sights on the Urdaibai Biosphere Reserve, intending to establish two locations there.

What is your relationship with the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation and under what circumstances and when?

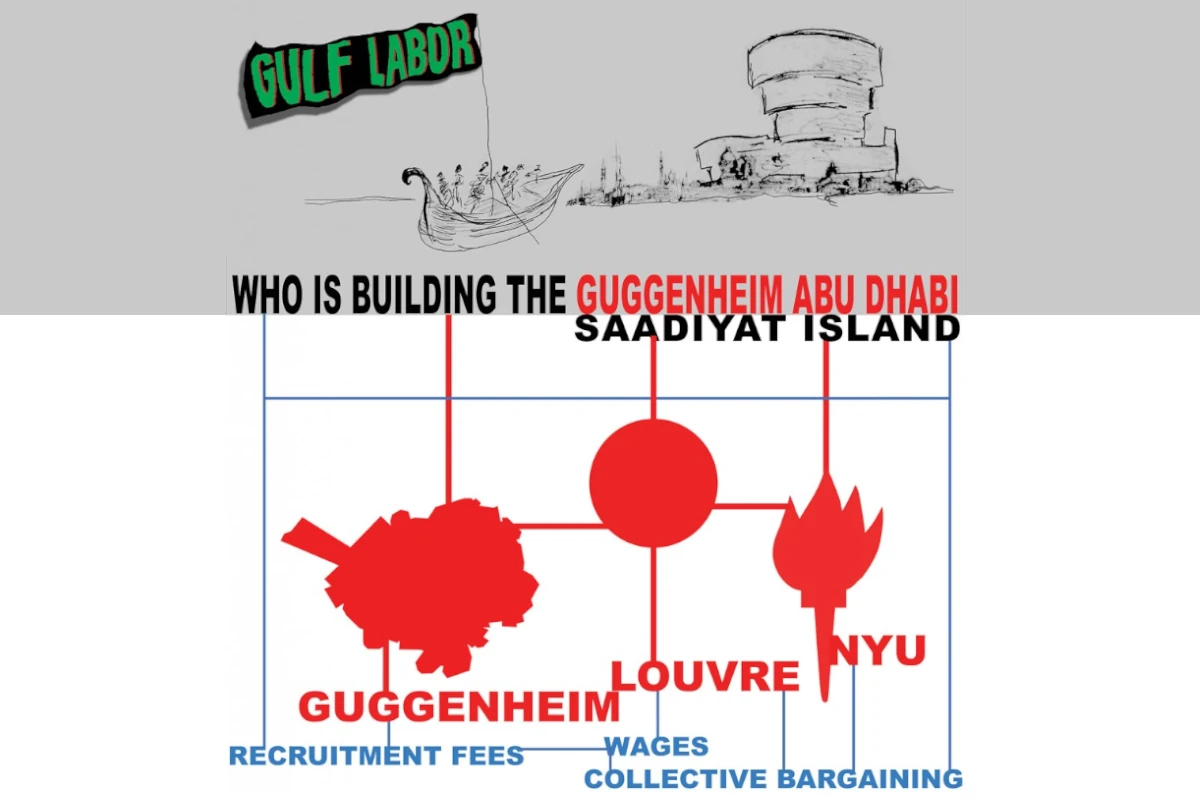

My own relationship with the Guggenheim dates to 2011, when I helped to establish the Gulf Labor Coalition, an international group of artists and critics, formed to combat the abuse of migrant workers in the United Arab Emirates. We chose to target the lavishly funded effort of the Abu Dhabi authorities to license some of the world’s top museum brands–the Guggenheim, Louvre, and the British Museum—for a new cultural quarter under construction on Saadiyat Island.

What interests do the Abu Dhabi authorities have in bringing such brands to Saadiyat?

These new branches were being acquired to add luster to the Emirate’s strenuous efforts to promote the national brand at the same time as they would help sell luxury villas on the island. In common with other Gulf countries, the UAE relies on vast numbers of mistreated migrant workers from South Asia to build out the infrastructure of its fast-growth emirates. “High Culture/Hard Labor” is the slogan we gave to the Saadiyat formula of arts-driven growth, and it rests on a simple moral principle–no one should be asked to exhibit, curate, or perform in a museum built on the backs of abused workers.

What references or previous experiences was your campaign based on?

Adopting the playbook of anti-sweatshop campaigners who sullied the brands of top garment producers, beginning with the Nike boycott in the 1980s, by exposing the misery of their subcontracted workforce, we decided to leverage the museums’ high-profile names in an effort to raise labor standards for the UAE’s migrant workers. Because most of the Gulf Labor core members were based in New York City, we had more local traction with the Guggenheim than with the Louvre or the British Museum. So, we concentrated on publicly pressuring the Guggenheim leadership in New York to adopt a model set of worker standards for others to follow.

How did you go about your campaign?

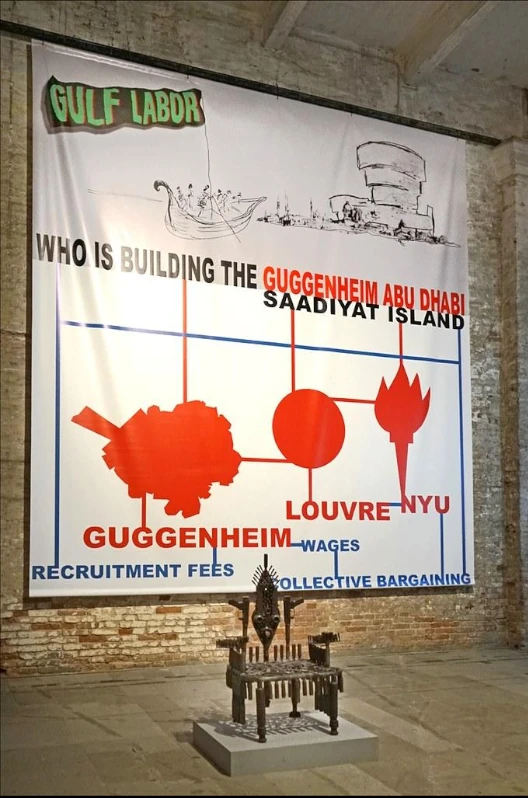

The campaign took many forms: an international boycott of the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi that attracted thousands of signatories from artists, critics, and curators; direct dialogue with the museum’s leaders and trustees along with the Abu Dhabi officials tasked with delivering Saadiyat Island’s cultural quarter; coordination of NGO and trade union partners to put pressure on the museum; field research in Abu Dhabi to take testimony from workers; publications and publicity in a variety of forums; a yearlong program of commissioned artworks called 52 Weeks; and direct action that involved a series of spectacular occupations of the Guggenheim in New York and Venice. The occupations were carried out by Gulf Labor’s direct action wing, G.U.L.F (Gulf Ultra-Luxury Faction), composed of comrades who had been active in Occupy Wall Street spin-offs like Occupy Museums and Strike Debt.

How would you characterize the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation? As a multinational art company? What are its fundamental interests?

Non-profit institutions with a financially acquisitive mission typically take on the characteristics of for-profit entities. In the Foundation’s case, the creation of its flagship New York museum and its Venice branch (in situ because Italy would not allow Peggy Guggenheim’s art collection to be exported) were both funded and stocked by family members. Ever since then, the Foundation has been trying to license the Guggenheim brand to cities and states. Its expansion model is built around franchising, and in this respect, it was the first large cultural institution to adopt and apply this corporate template, pioneered in retail.

Their expansion plans have touched nearly every continent and numerous cities. Many were ruled out from the start, others went through many back-and-forths before ultimately being abandoned, and a few got the go-ahead: Venice, Bilbao, and now Abu Dhabi. What is their approach in the processes they initiate?

The expansion built on the museum boom of the 1990s and 2000s, which was driven by the doctrine of culture-based development. Many of these museums were built in depressed, low-income neighborhoods, they involved demolition and population displacement, and public money was allocated on the basis that culture was not so much an instrument of class uplift –as it was understood to be in the conception of classic 199h century museum–but more of a catalyst or vehicle for economic recovery and rejuvenation.

Is there any kind of pattern in how it goes about this?

This boom was a global one, and driven by a combo of speculative art world economy (from the top down) and the revitalization strategies anchored by landmark neighborhood catalysts (from the bottom up). The Guggenheim Bilbao took this paradigm to the next level of regional regeneration. The museum has been touted as the savior of an economically depressed region, though, from what I know, most of the reputable studies of the Bilbao Effect suggest that the revitalization was mostly a result of the $4b public money invested in city infrastructure, waterfront and business real estate development. Subsequently, the Foundation launched a worldwide search for cities that would pay for feasibility studies, licensing fees, and potentially, vast operating subsidies. Most of the ventures fell through or were never built, but the Foundation continued to take in revenue regardless of the outcome, and circulate its brand name, again, regardless of the outcome. So the brand franchising has generated revenue even when it failed to result in a building. That is its business model, if you will. It is relatively flexible, so there is not a cookie-cutter product, like a McDonalds franchise.

What can you tell us about the case of Abu Dhabi?

The Guggenheim Abu Dhabi was envisaged as an amenity of Saadiyat Island, where Abu Dhabi’s Tourism and Development Corporation (TDIC) was planning the mother of all luxury property developments. Saadiyat’s plush real estate was to be sold on the premise that buyers can stroll to branches of the Guggenheim, the Louvre, and a new national museum partnered with the British Museum. To add to the cachet, a batch of lustrous starchitects—Frank Gehry, Jean Nouvel, Zaha Hadid, Raphael Viñoly, Tadao Ando, and Norman Foster—were lured with princely sums to design the signature buildings.

Saadiyat Island was Abu Dhabi’s effort to diversity its economic profile beyond petroleum production into the tourism, real estate, cultural, and recreational sectors. The Emirate basically bought the top cultural brands, including that of my own employer New York University, whose offshore branch campus opened on the island in 2010, as part of its state-building enterprise. Each of the institutions received a vast sum in return, and all of the construction and building maintenance was bankrolled by Abu Dhabi. In the case of the Guggenheim, a first-class collection of Arab and Middle Eastern art was scouted and purchased an enormous cost.

At this point I would like to talk about labor exploitation, both of the initial labor force and of the workers who later become part of the Museum… Under what labor and economic conditions do they do so?

All the Gulf countries use some version of the kafala (sponsorship) system of worker recruitment. Under the kafala regime, workers arrive heavily indebted and tied to their sponsor or employer–with few labor protections, they are subject to harsh work discipline and surveillance, and are beaten and deported if they complain or go on strike. The associated labor camps and punishing working conditions all have colonial roots in a region with a long history of authoritarian rule, implanted by foreign powers and perpetuated internally by absolute monarchies.

Our goal, in the Gulf Labor Artists Coalition, was to raise labor standards and conditions for the migrant workers in the UAE and the Gulf generally. After other NGOs like Amnesty and Human Rights Watch were banned for prying into the labor question, we were the only outsider group collecting field testimony from the workers. Myself and several colleagues were eventually barred entry in 2015. But the construction of the Guggenheim was stalled as a result of our efforts for several years, and is now tainted by association. In other words, there was a price to be paid for the systemic abuse.

In the interim, the focus on labor rights of the construction workforce of museums has been expanded to the institutional workforce itself. Museums have become the site of a wave of labor organizing, with unions and collective bargaining won at institution after institution. We supported the worker initiatives at the Guggenheims in New York and Bilbao.

And what happened with the Helsinki Museum that was planned and ultimately not built? Can you tell us something about the Helsinki Effect?

Shortly after the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi project ground to a halt, the architect Michael Sorkin and I ran a related campaign along with members of the Finnish arts community to oppose the Guggenheim’s plans for another museum branch in Helsinki. We staged an architectural competition as an alternative to the official competition run by the Guggenheim. Ours cost five thousand euros, while tens of millions were spent on the official competition. In our view, Helsinki did not need to be put on the arts map by a blockbuster titanium-clad starship cruiser museum, it was already bursting with artistic creativity. The city did not need an influx of cruise-ship tourists for whom a museum visit to see the works of non-Finnish artists would be their only engagement with Helsinki.

In opposition to the Guggenheim model of culture-driven development to stimulate tourism and the like, we organized our alternative competition around the principle that the arts and artistic activity can and should be an integral part of a socially just city, part of the public environment which a progressively minded population expects to enjoy.

And what happened after this competition?

In the end, we were able to block the museum plan by mobilizing trade unions to lobby the city council to reject the winning entry in the official competition. Building on our work in Abu Dhabi, we were able to associate the Guggenheim name with human rights abuses—a taint that the city, pressured by the trade unions, were unwilling to host.

It seems curious and even contradictory that a Foundation with such liberal characteristics, with a strong capitalist sense, is interested in being financed by public funds… as has happened with the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao.

Not at all. As a rent-seeking entity, the Foundation will take any subsidy that comes its way. The Helsinki plan was anchored by a hefty public subsidy, but it was to be built out by private Finnish capital, much of it coming from wealthy people heavily invested in right-wing nationalist causes. Some of this private money had already been pledged, but when the city was unwilling to extend the initial outlay, the Foundation withdrew. Abu Dhabi was public money all the way, and Bilbao was also largely paid for by the Basque Government. The Foundation is a non-profit entity but it is also a non-philanthropic enterprise whose institutional momentum is driven by the appetite for expansion and brand promotion. In that respect it behaves no differently from a corporation trying to grow its revenue. The managers of private university endowments in the US think and behave in the same manner.

Why do you think that the Guggenheim in Urdaibai option is of interest to the Foundation?

No doubt the Foundation thinks that Urdaibai could replicate, or at least enhance, the reputational glow delivered to the museum by the Bilbao Effect. Urdaibai seems to be already within the itinerary of tourists for whom the Bilbao museum is a draw. So, to offer a second arts destination along the way makes economic sense. And for the government officials focused on regional regeneration, they are surely enamored at the prospect of tourists extending their visit by at least a day to take in another museum visit. The zeal of a local government to bring the Guggenheim and support it lavishly with public funds is a prerequisite for any global branch of the museum. They don’t have to spend time and money persuading officials. Last but not least is the prospect of being able to bring Picasso’s painting to Gernika, where it has never been exhibited. The Spanish government has long been reluctant to allow it to travel outside of the Museo Reina Sofía, but I am sure that the Guggenheim’s managers are salivating at the notion that they might be able to pull off this coup.

What do you think of this link that is intended to be established between Art and Nature to better sell this idea, precisely in a place where the biodiversity of this natural space is seriously endangered?

The economies of cultural tourism and nature tourism tend to be separate circuits, with different kinds of customers. But there’s some overlap, and, with sufficient numbers, there’s no reason why it could not work as a “value proposition.” Of course, the environmental hazards of eco-tourism are well-known to host communities, and in the case of Urdaibai, the threat is well-documented. European cities, including Bilbao, are already groaning under the weight of overtourism and we are seeing a popular pushback against the suffocating impact of the tourist economy. In many places, this paradigm of economic development is collapsing. It seems imprudent for the local government to be placing their faith in it at this point in time.

Last year the Guggenheim R Solomon Foundation appointed a new director, Mariet Westermann. What can you say about her?

We were at loggerheads for many years when she was a lead administrator at NYU Abu Dhabi, and I was active in our Fair Labor Coalition that was intensely critical of the building and operation of the campus. Our report on forced labor at NYU Abu Dhabi came after the university’s reputation was badly damaged by revelations about labor abuse in its construction. Westerman had been a player in Abu Dhabi for many years before she was appointed vice-chancellor in 2019, and so she acquired a great deal of expertise as a go-between with the Abu Dhabi government. As an art historian and a close witness to how the Foundation operated in the Emirate, she was a natural choice to take over as president.

Do you think that it could be a great political cost for its promoters to carry out this project?

There is always a smell of corruption around any decision to devote so many public funds to a private beneficiary. If things go awry, then officials will have to face the music. Most of the Foundation’s plans for global branches have indeed fallen through, and “local investors” have taken a hit, so this may well happen in Urdaibai. So, too, if the museum gets built in such a fragile eco-system, the burgeoning protest movement that targets museum artworks will have a new mark on their list.

1 Gulf Labor Coalition, https://gulflabour.org/: Negar Azimi, “The Gulf Art War,” New Yorker (December 11, 2016), https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/12/19/the-gulf-art-war.cember 11, 2016.

2 Andrew Ross (for Gulf Labor), ed., The Gulf: High Culture/Hard Labor (New York: OR Books, 2015)

3 Colin Moynihan, “Labor Protesters to Resume Guggenheim Demonstrations,” New York Times (April 17, 2016), ttps://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/18/arts/design/labor-protesters-to-resume-guggenheim-demonstrations.htm

4 Gulf Labor also spun off an architecture wing, called Who Builds Your Architecture?, aimed at establishing ethical labor standards in the architectural world. See Who Builds Your Architecture?A Critical Field Guide, http://whobuilds.org/who-builds-your-architecture-a-critical-field-guide/